Ever wonder why all the folks you know from your college are either athletic/

artistically-talented (and all the adjectives synonymous with cool) or academically

overachieving but never both, and there seems to be some negative correlation between

coolness and academic gift? Some might find a few super rare schoolmates who are both

but the truth is they shouldn’t be in the school and I will tell you why.

Although this correlation is often accepted to be conventional wisdom (Thanks God it’s fair 😮💨 no one can be both cool and smart), we’re staring right at the face of a logical fallacy - namely Berkson’s Paradox.

So what the hell is Berkson’s Paradox?

To avoid being called a math nerd (which I am a huge one admittedly), let’s keep the definition of Berkson’s paradox simply a false observation of negative correlation between two positive traits.

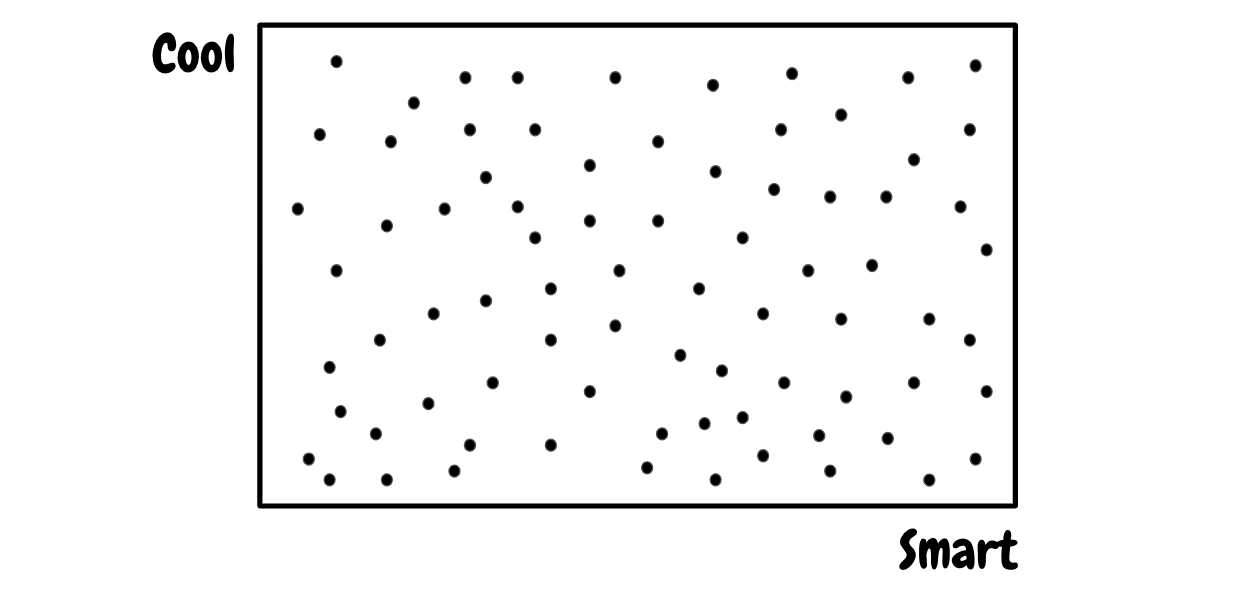

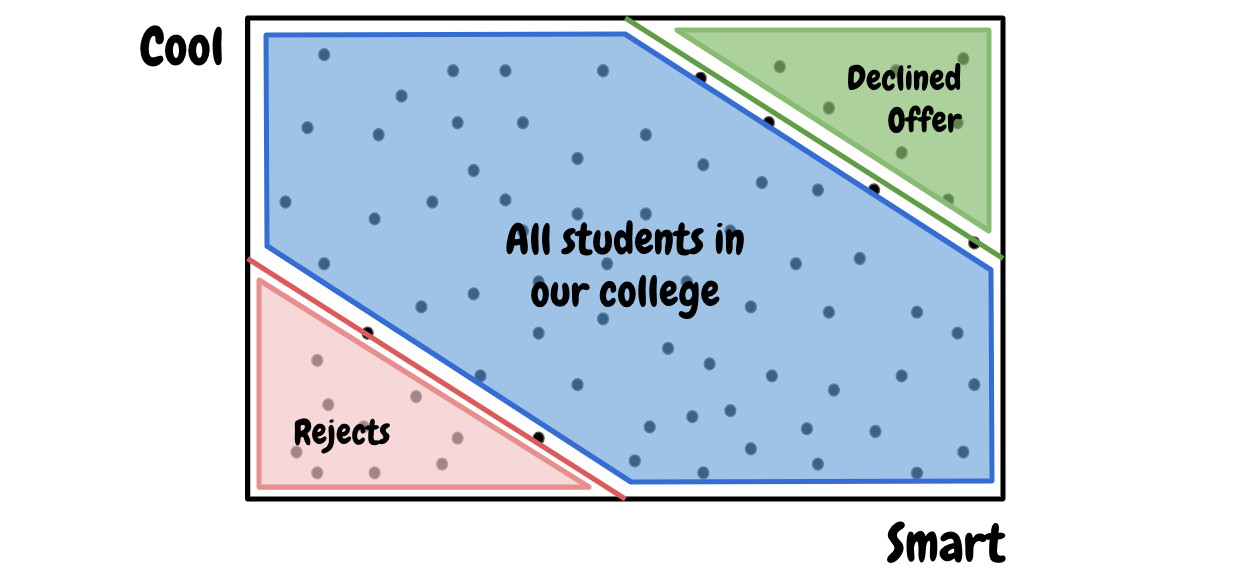

Let’s take a look back at the example we started the article with - the negative correlation between coolness

and smartness in college - and start with the pool of applicants to the school. Assuming there’s no prohibition

on whom can or cannot send in an application, we will have an evenly-distributed pool of applicants on both cool and smart scale.

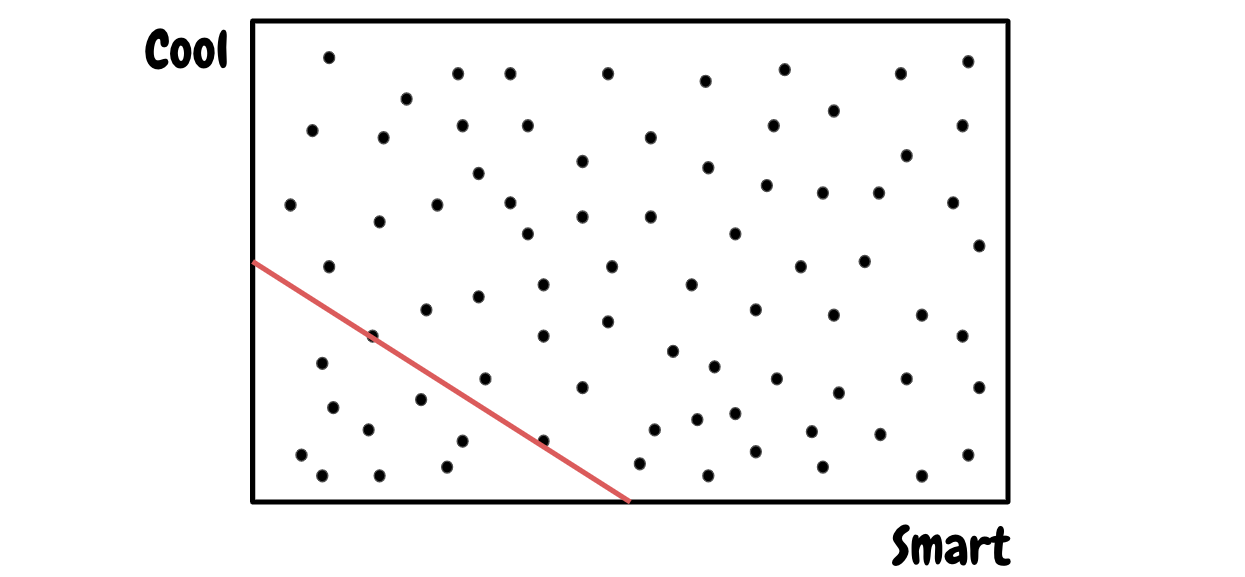

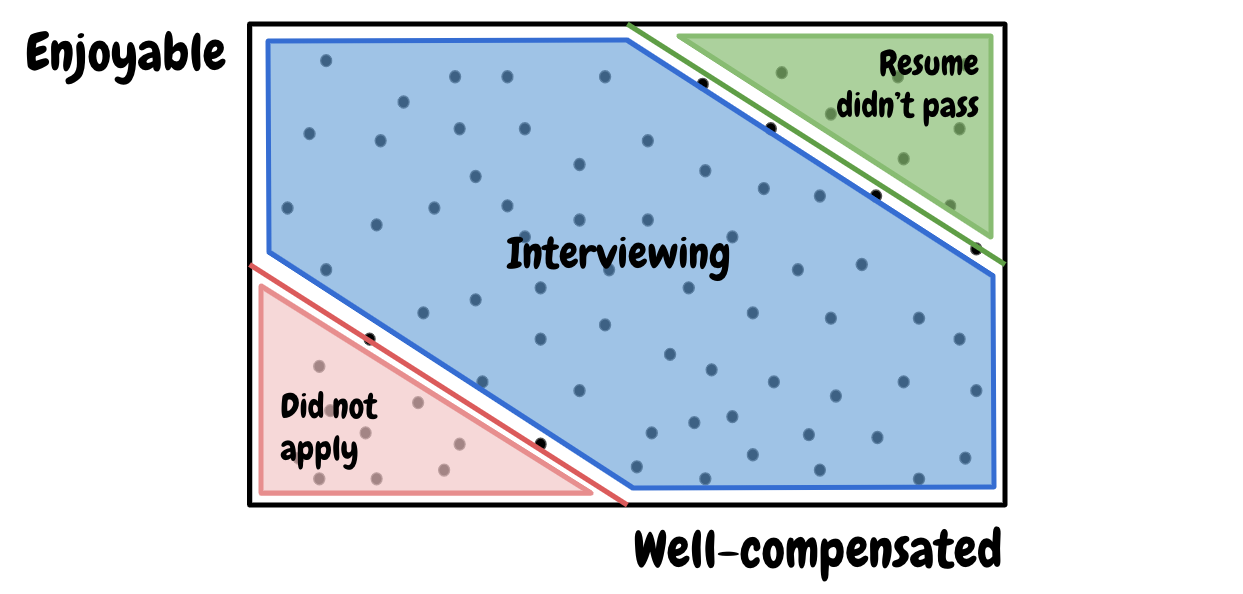

But of course, our alma mater wouldn’t be able to accept every single applicants to be their students. So as part of the recruitment process, a line (red) is drawn of which only students on the right are offered a place to the college.

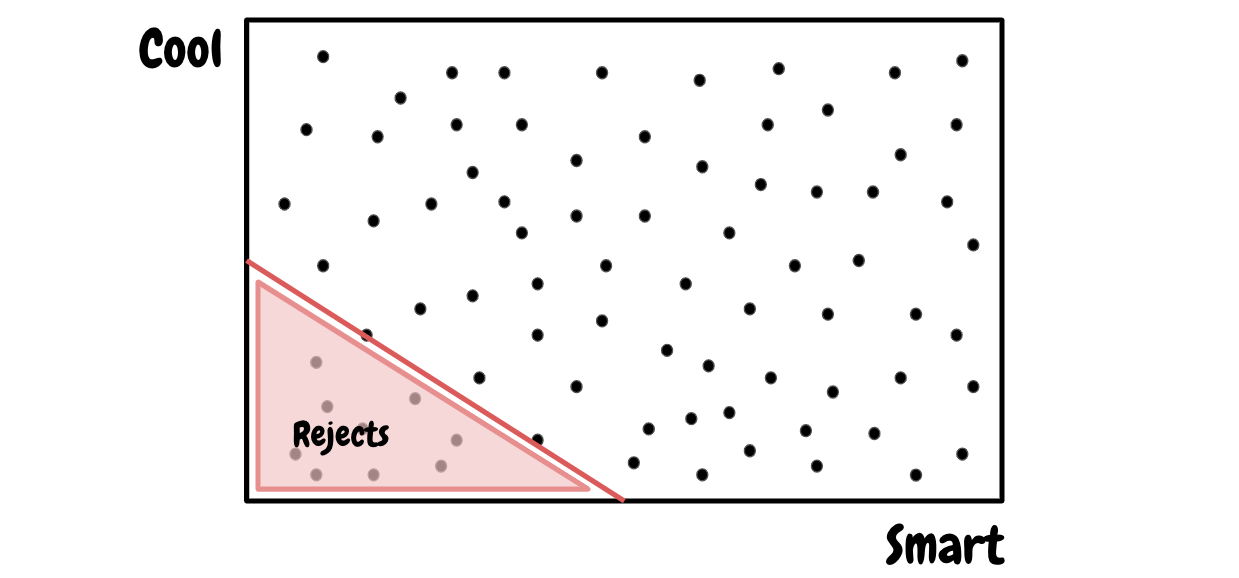

To make it even clearer, let’s annotate the entire area

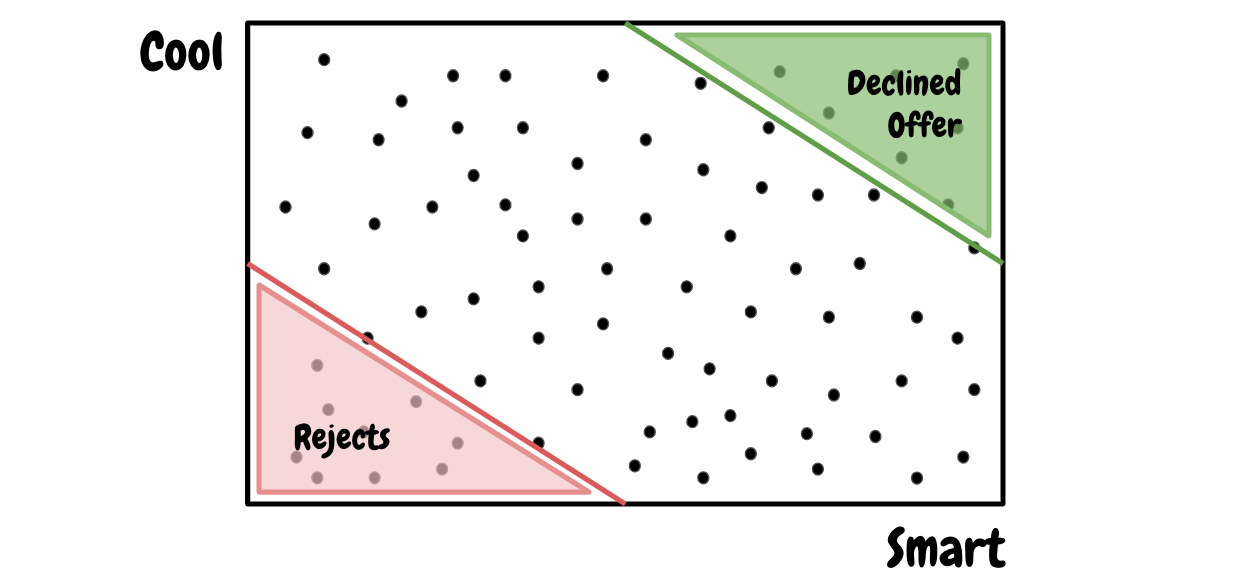

On the other hand, there would be applicants who are offered a place but decline the offer for places in better schools. Logically, these applicants would be on the top right corner of the applicant pool (in green).

And that leaves us with our college’s student body (in blue)

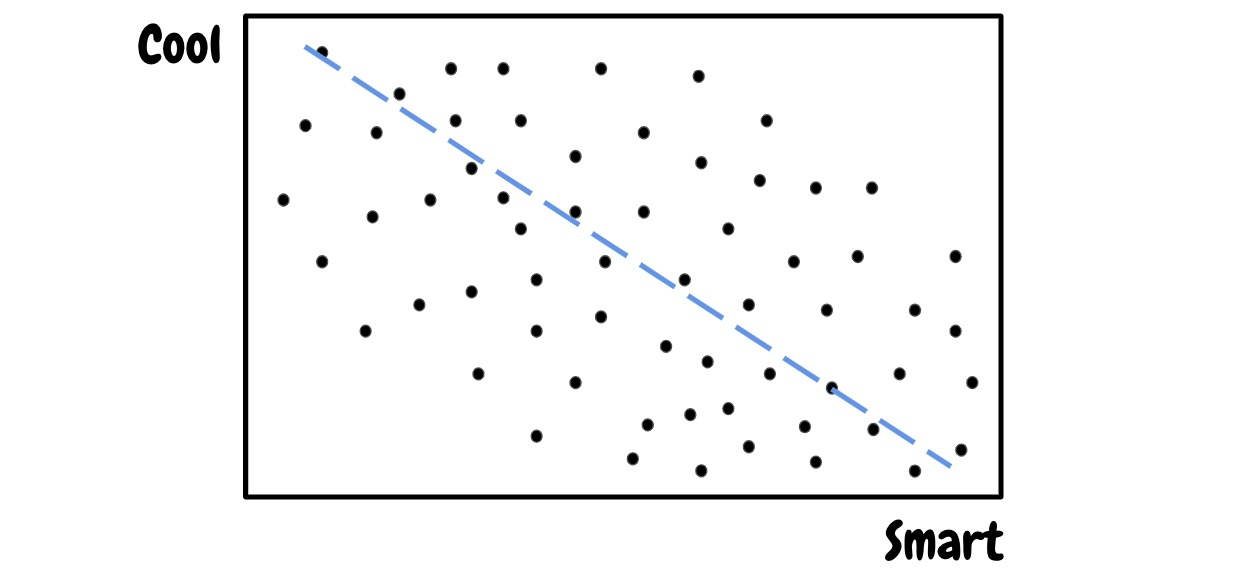

This student body is what we draw our conclusion from looking at, and obviously there is a clear negative trend between coolness and smartness.

However, what’s not so obvious is that we’re only looking at a subset of all prospective students of our alma mater, instead of the whole picture.

And that, my friend, is what we call Berkson’s paradox - a false observation of negative correlation between two positive traits caused by an incomplete identification of data points.

How do we view life through the lense of Berkson’s paradox?

Now let’s get to the part we’re all most excited about - applying Berkson’s paradox to our lives (or maybe just plotting friendzone on a graph 😂 either one is cool, no judgement).

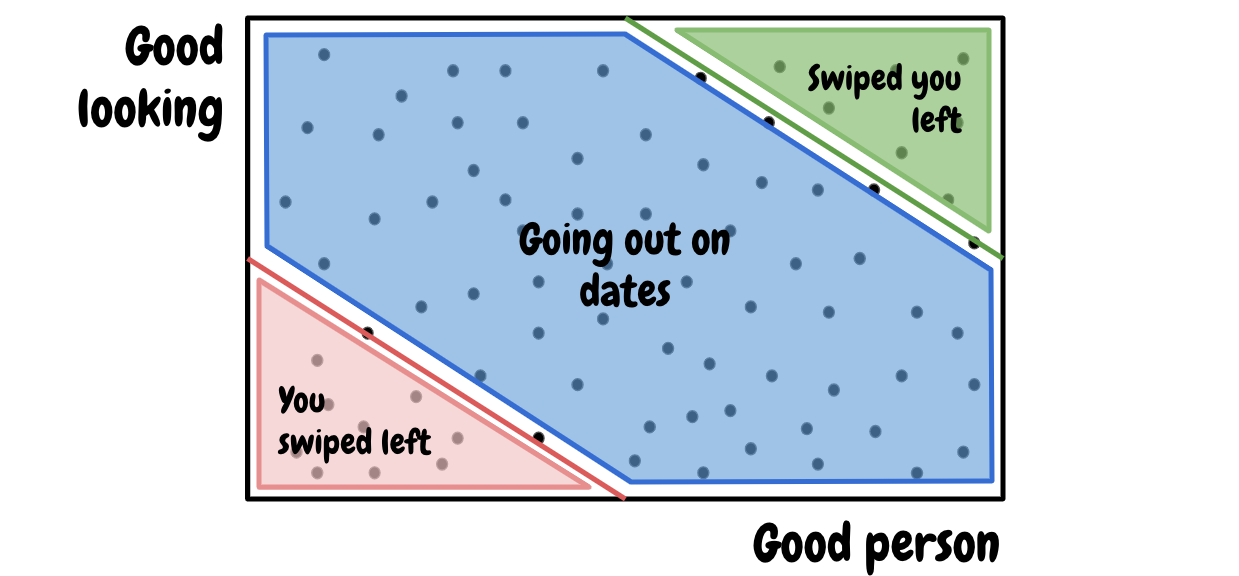

For the example to be relatable and exciting, we’re going to apply Berkson’s paradox to the human phenomenon of dating. Similar to the above example of our college’s student body, we are going to split up our population into 3 segments. (I’m just going to assume everyone who is reading is familiar with dating apps like Tinder)

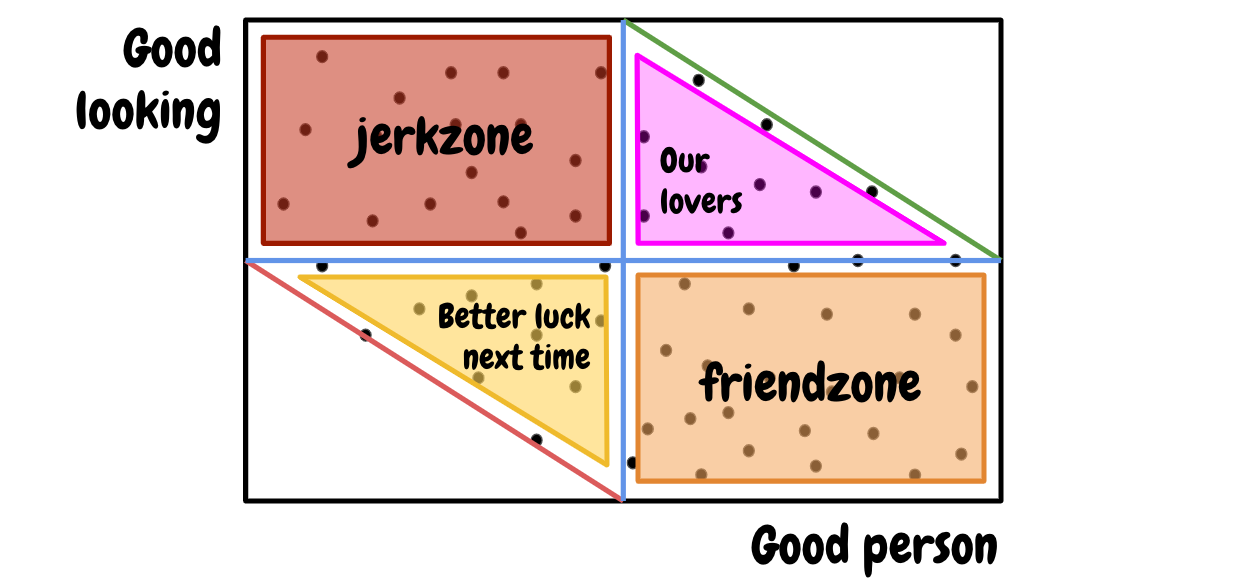

Before you raise your pitchforks while screaming “where is the friendzone?” at me, let’s further segment our dates and potential lovers with into 4 more elaborate sections.

Out of all those who we deem acceptable to go out on dates with, there must be those who are:

- Decent-mannered and decent-looking human-beings (who can eventually become our lovers)

- Decent-looking but not much of a good person (the jerkzone)

- Good person but not good-looking enough (the infamous friendzone)

- Falling short on both aspects (Better luck next time!)

Even under this more elaborated segmentation of the dataset, the eventual segment that will likely be taken into consideration by most of us, our lovers (purple triangle), displays a negative correlation between being good-looking and being a good person too. So next time if you hear someone complaining about why they can’t find someome attractive who is also a good person, show them this post and let them know that it’s just a logical fallacy and their Mr./Ms. Right is out there, just not in their zone, not yet.

How is this related to growth mindset?

Very much the same concept can be applied in a lot of other aspects of our lives too, like this one I have below for our career.

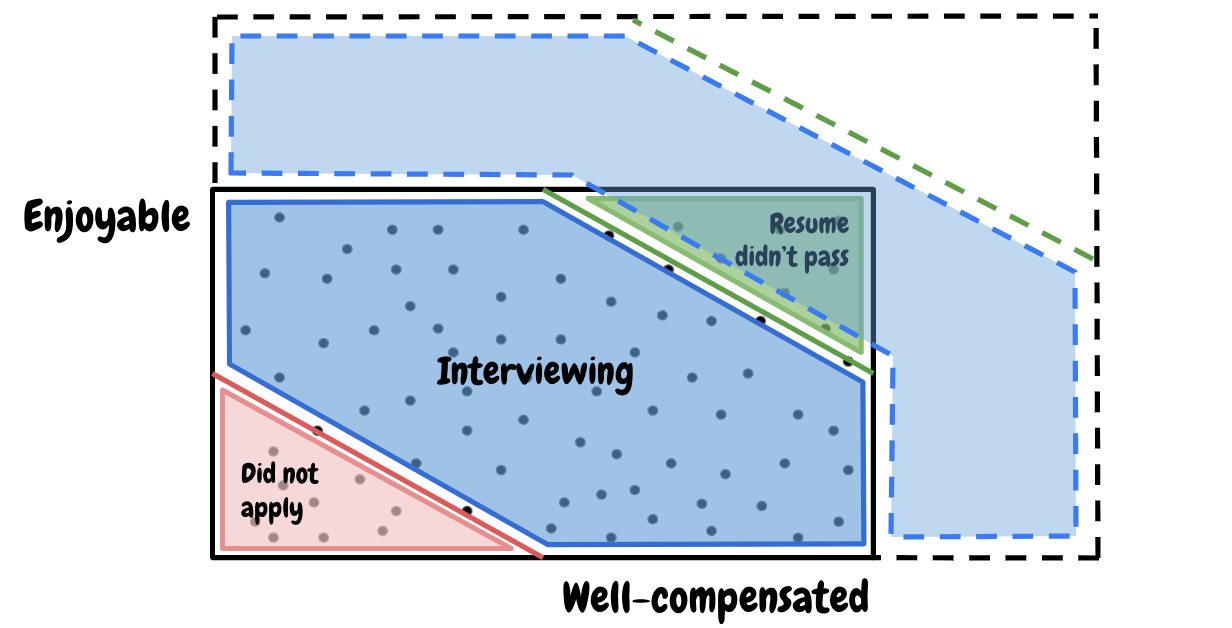

So what can we do knowing this logical fallacy? The most logical answer for an objectively better outcome of more career opportunities, or potential lovers is to expand the area of the blue segment towards top right corner. There are 2 ways of doing this looking at our graphs:

- Moving the green line to the right

- Expanding the boundary box’s top and/or right borders

Just look at how much better we can possibly do (dotted blue area)

So what do both of these visual “actionables” mean in practical terms? “Moving the green line to the right” is basically working on improving yourself so you can be eligible for overall-better jobs, or much more a prize of a date. “Expanding the boundary box’s borders” means meeting more people, getting out of your comfort circles.

Now some of you smartypants might have noticed and pointed out that as we progress ourselves, our expectations, represented with the red line, might shift as well and we might end up depressed again. I’d say that at least this way we’re better off in absolute terms, and as human-beings, we will always be cursed with “not getting what we want or getting what we wanted then not knowing what we want”. It’s going to take another post to explore this human psyche so I’m going to end this post here before I start sounding like a motivational speaker instead of a math nerd, of which I would pick being a math nerd any day over.